The unLost Art of Pilgrimage

By Ivan March

Lips are cracked, the mouth is dry. The wind is kicking up dust, you’re chewing the air along with some of the dirt you just inhaled. There are a lot of bodies around you, sweat-soaked and baking in the heat. Your sleepless body vibrates to the groove. Surrender, release, blockage, confrontation, confusion, pride, resistance, conditioning, unconditioning, exhilaration, liberation, grief, freedom, griefreedom. You’re trying to free your mind, so that your ass may follow. Eventually you collapse into your tent, teepee or on the ground, beside your exhausted companions only to start again soon. You most likely traveled far to subject yourself to this experience.

Why?

Because whether you acknowledged it or not, you’re on a pilgrimage.

Perhaps you’re a raveteran, perhaps you were gifted a ticket, perhaps it’s your first time at a festival. No matter which is your perhaps, you are pilgrimaging. A festival is a commitment. Getting there is a challenge. Staying there for days on end is a ride. Returning to default reality altered is a balancing act. The whole quest of ‘there and back again’ is a pilgrimage.

Pilgrimage /ˈpɪlɡrɪmɪdʒ/ noun. A journey, often into an unknown or foreign place, where a person goes in search of new or expanded meaning about their self, other selves, nature, or a higher (or lower) power, through the experience. It can lead to a personal transformation, after which the pilgrim returns to their daily life. Some pilgrimages repeat, oftentimes once a year, others are singular rite-of-passage-style pilgrimages (like walkabouts or vision quests). The muslims go to Mecca, the jews to Temple Mount, the hindus to Varanasi, the buddhists to Bodh Gaya, the christians go to Jesus camps, Lord of the Rings fans go to New Zealand and audiophiles go to music festivals.

Seeking the Strange

Petrarch (an early Renaissance poet who loved wearing laurel leaves around his head), wrote in the 14th century, ‘‘I do not know whence its origin, but I do know that innate desire to see new places and to change one’s home. There is something truly pleasant, though demanding, about this curiosity for wandering through different regions.’’ Pilgrimage is a way to construct your identity, to map the outer limits of your inner world, and the old cliche holds true, sometimes to find yourself you first need to get lost. Festival goers certainly fit this bill, since festivals probably have the highest density of lost-looking people on the planet. It’s not just the psychedelics, it’s the drive to seek the hidden, and a good festival is like a layered treasure hunt, the most memorable lessons you take with you are the ones you didn’t know you had to learn.

Theology prof, Frederick J. Ruf writes about the strong human ‘‘desire to seek the strange’’, he writes of the benefits of confusion, of the non-linear path, of “moving us beyond ourselves into the radical potentialities of disorientation” – you disorient to orient. Anthropologist Jill Dubisch adds that pilgrimage is “journeying away from home in search of the miraculous” and that is what is on offer at a festival, a constant supply of miracles, whether real or imagined, even the ability to imagine out-of-the-ordinary situations is at peak capacity. These liminal spaces between reality and fantasy are seductive because our dreams blur with our waking life.

“The interchanges between a place and its community of people are what make a place holy.” Ryosuke Okamoto reminds us of this in his ‘Pilgrimages in the Secular Age’. People are placing more importance on the shared image and experiences expected to be had there. “In the past, holy sites were of immense importance to those who followed a particular religion, and these places used to attract many faithful pilgrims. These days, however, people without faith visit holy places simply to experience something out of the ordinary. Furthermore, many places without any connection to religion are being called ‘sacred’ and attracting people’s interest. From the Camino de Santiago in Spain, to Burner HQ in Black Rock City Nevada, to Elvis’ grave in Memphis or sacred anime sites, humans of the twenty-first century are hungry for meaning and new rituals, and transformative music festivals already contain the symbolic and spiritual architecture needed to accommodate this need.

“Pilgrimage is understood generally as a journey from the daily life of the individual, the mundane and quotidian, so to speak, to a sacred world” (Bhardwaj and Rinschade 1988) and for us growing up in secular contexts, we need to find what is sacred to us out in the world.

From Movement to Groovement

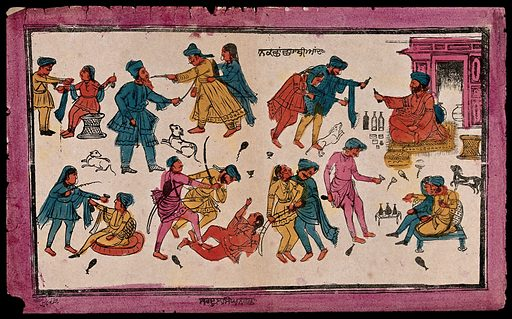

For Hunter S. Thompson and every committed raver, music is food – “Music has always been a matter of Energy to me, a question of Fuel. Sentimental people call it Inspiration, but what they really mean is Fuel. I have always needed Fuel. I am a serious consumer. On some nights I still believe that a car with the gas needle on empty can run about fifty more miles if you have the right music very loud on the radio.” Pilgrimage is unimaginable without music. Music-song, chant, prayer, procession, dance, – provides the essential material to narrate and guide each pilgrimage. Ethnomusicologist P.V. Bohlman writes that “through music, the pilgrim embodies the way along which he or she passes during the course of a pilgrimage. Song has historically provided one of the most powerful means of inscribing pilgrimage, thereby transforming the music of pilgrimage into one of the most powerful means of recording history. Faith and history intertwine in the music of pilgrimage, transforming it into a site for sacred and secular practices.” Whether in the Bacchanalia of Ancient Rome, Chaucer’s medieval England, or warehouse free parties in Newcastle in ‘90s, the beats held the community together, they connected through the music, to themselves and each other.

Mixed Beans 2, 1993 © Abel

For a while now, both political figureheads and rebellious dissenters have been tugging at the vast majority of people to go in one direction or another. Usually two sides of the same corrupt, bullshit coin. Right versus left. Macho versus snowflake. One hypocrite versus another hypocrite. Shitty binaries that feel like a choice but are not really choices. Movement builders, even the very well intentioned ones, have to have strong attachments to a direction, a prescription, a “I’ve seen the light and let me take you there’’. They have a mission to get some place and they march towards it. After years of disillusionment and disappointment at false prophets or gifted folks who sing songs of utopias and promised lands, non-directionality seems most exciting. Simply not having to get anywhere seems like the most revolutionary act at this point in time. Not buying into a binary or a direction. Just staying put. Just being. Contemplating. Reflecting. Vibrating. Perhaps trying to vibrate at a different frequency but not obsessing with getting somewhere. That’s where the groove comes in. It takes you places while you stay put. It’s a form of transcendence. Of going beyond, without going. We are in desperate need of fewer movements and more groovements.

Quality over Quantity

But staying put is terribly tricky for modern man’s monkey brain. We live in an age of addiction and distraction. If we didn’t, Gabor Mate wouldn’t be a household name. We are addicted to novelty, to sensation, to experience. We are addicted to speed, pace, velocity. The headless chicken effect is not rare on a festival site. Too much choice, and not enough discernment. We have sacrificed quality for quantity and we’re paying the price. Our ADHD-frazzled brains are worrying about FOMO and they’re missing out on what’s in front of them while being worried about missing out on what’s somewhere else.

The pilgrimage is a way of slowing down, of savouring the journey, of realising that the journey is an essential part of the experience – essential. Let your senses feast on the festival. That feast starts with the moment you start packing your bag in your head. That journey of a thousand miles starts with a single step, so don’t just cherish the climax. And stop with the linearity, the binaries, the beginnings and endings. When does the festival end? When does the pilgrimage end? When the last beat drops? When the music ends? When you pack your tent? When you hitch a ride to the airport? When you come down from that last quarter tab that was actually 300µg? When you get back to your bed? When you stop dreaming about your festival experiences? (spoiler: that won’t ever happen)

Will the pilgrimage you’re on end when you start the next one? Perhaps then, or perhaps your pilgrimages just stack, and your life ends up being a layer-cake of pilgrimages, all intertwining in your memory banks in quantum confusion, calendar years being much less important than the things that transpired, the fears that were confronted, the friendships made, the dancefloor kisses and the chemical mirages that remain carved in your brain.

At Journey’s End

A hobbit once asked, “don’t adventures ever have an end? I suppose not. Someone else always has to carry on the story.” Aside from life, festivals are the ultimate choose-your-own-adventure game, a vital expression of agency and free-will (if we step out of The Matrix). But as Hunter reminds us “freedom is something that dies unless it’s used” and not everyone is ready to use their freedom. Choosing one thing means losing others and coming to terms with that is a major life lesson. But pilgrimages are a means of processing such a lesson.

If life is the trip, then death is the final destination, and it’s not a destination most of us are particularly keen on getting to. Our confrontation with death is constant. If not the final, literal death, then a more figurative version in that every decision we make, all others die. Choosing to take the bus means that in that moment all other travel options have died. Choosing to buy a festival ticket, or to gatecrash a party, or to quit your job, or to dive into a lake naked are all freedoms of pursuit and deaths of other possibilities. Learning to live with and accept your choices, while learning from the ones made so you can find more contentment in future ones feels like an essential part to growing up, and many of these skills are learned and integrated in dusty campsites and endless toilet queues.

Pilgrimages of some sort appear in most religions, Sikhism however represents a refreshing, rebel religion in this case. Sikhs do not consider pilgrimage as an act of spiritual merit. In the 15th century, Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, traveled to places of pilgrimage to reclaim the fallen people, who had turned ritualists. He told them not to look for God in sites and temples, but deep in the inner being of themselves. According to him: “He performs a pilgrimage who controls the five thieves.” The five thieves being: kaam (lust), krodh (wrath), lobh (greed), moh (attachment) and ahankar (ego or excessive pride). Pilgrimage was not to be found in the material world but in the mind, in the landscape of the soul. Ahankar or ego, is deemed the most dangerous of the thieves, and so naturally, since Woodstock the most common festival sacrament, LSD, has quite the reputation as an ego dissolver.

Ancestral Footsteps

Dissolving the ego is not the end of the lesson (if there is a lesson to be found here). “The sacred site is the goal of the pilgrim, and its meaning within religious practice necessarily extends to the journey leading to it.” (Eliade 1963)

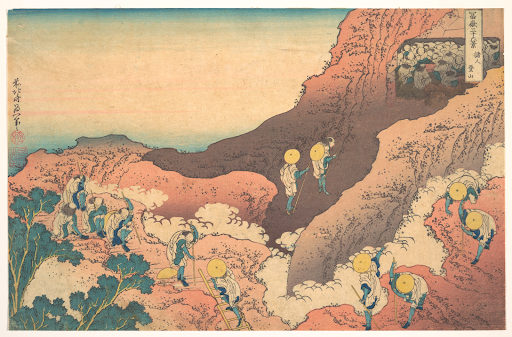

The big mama of ritualised ecstatic practices, the Eleusinian mysteries, also included a pilgrimage. Young initiates were guided in a walking procession to the site of Eleusis, starting at the Athenian cemetery Kerameikos along the Sacred Way (Ἱερὰ Ὁδός, Hierá Hodós). In Athens today, Iera Odos is still the name of this road, except now it is lined with sex shops and brothels – the sexual component of the cult remains alive to this day.

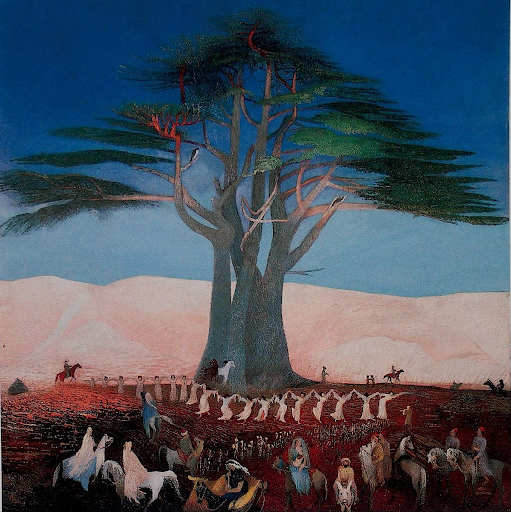

The cult dedicated to Dionysus as god of ecstasy, wine and ceremonial madness, originated from agrarian protocults dedicated to various incarnations of ‘the earth goddess’ (Baldini 2015). The 11 day ceremony and induction into the cult involved two processions, or pilgrimages, long walks that allowed for the initiates to prepare for the moment of deep altered states and the walk afterwards — this symbolized the double nature of the festival. The material and the immaterial. Such journeys offered initiates a ‘re-enchantment of places that once were sacred’. Dancing to the beat of the shamanic drum, consumption of herbal psychotropic concoctions, and engagement in collective sacred sexuality in a pastoral setting has been a major vibe for devoted pilgrims for millennia.

In pilgrimage, the body-soul distinction becomes irrelevant; souls and soles are not just homophones. Part of why examinations of pilgrimage are important, like the ones offered here, is that they reveal how religion itself is vitally physical.

The sisyphean struggle. The never-ending story.

One. Stepping out of the mundane into the extraordinary.

Two. Vibrating at a different frequency.

Three. Appreciating the trip but not getting tied down to it. Taking it lightly.

Four. Confronting fears, ultimately of your own physical demise.

Five. Draw strength from ancestral lineage, nice to know you’ve got ancestors, all went into trance, trancestors, they’re your spiritual crew.

Six. Turning the mundane into a mundance. The pilgrimage within.

Onward, pilgrims.

References

Baldini, Chiara (2015) The Politics of Ecstasy: the Case of the Bacchanalia Affair in Ancient Rome, Neurotransmissions: Essays on Psychedelics from Breaking Convention.

Bohlman, P. V. (1996). Pilgrimage, Politics, and the Musical Remapping of the New Europe. Ethnomusicology, 40(3), 375.

Coleman, Simon, Eade, John (2004), Reframing pilgrimage : cultures in motion. European Association of Social Anthropologists. London: Routledge.

Nielsen, Inge (2017). Collective mysteries and Greek pilgrimage: The cases of Eleusis, Thebes and Andania, in: ‘Excavating Pilgrimage’.

Okamoto, Ryosuke (2019). Pilgrimages in the Secular Age: From El Camino to Anime. Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture.

Plate, S. Brent (September 2009). ‘The Varieties of Contemporary Pilgrimage’. CrossCurrents. 59 (3): 260–267.

Reader, Ian; Walter, Tony, eds. (2014). Pilgrimage in popular culture. Palgrave Macmillan.